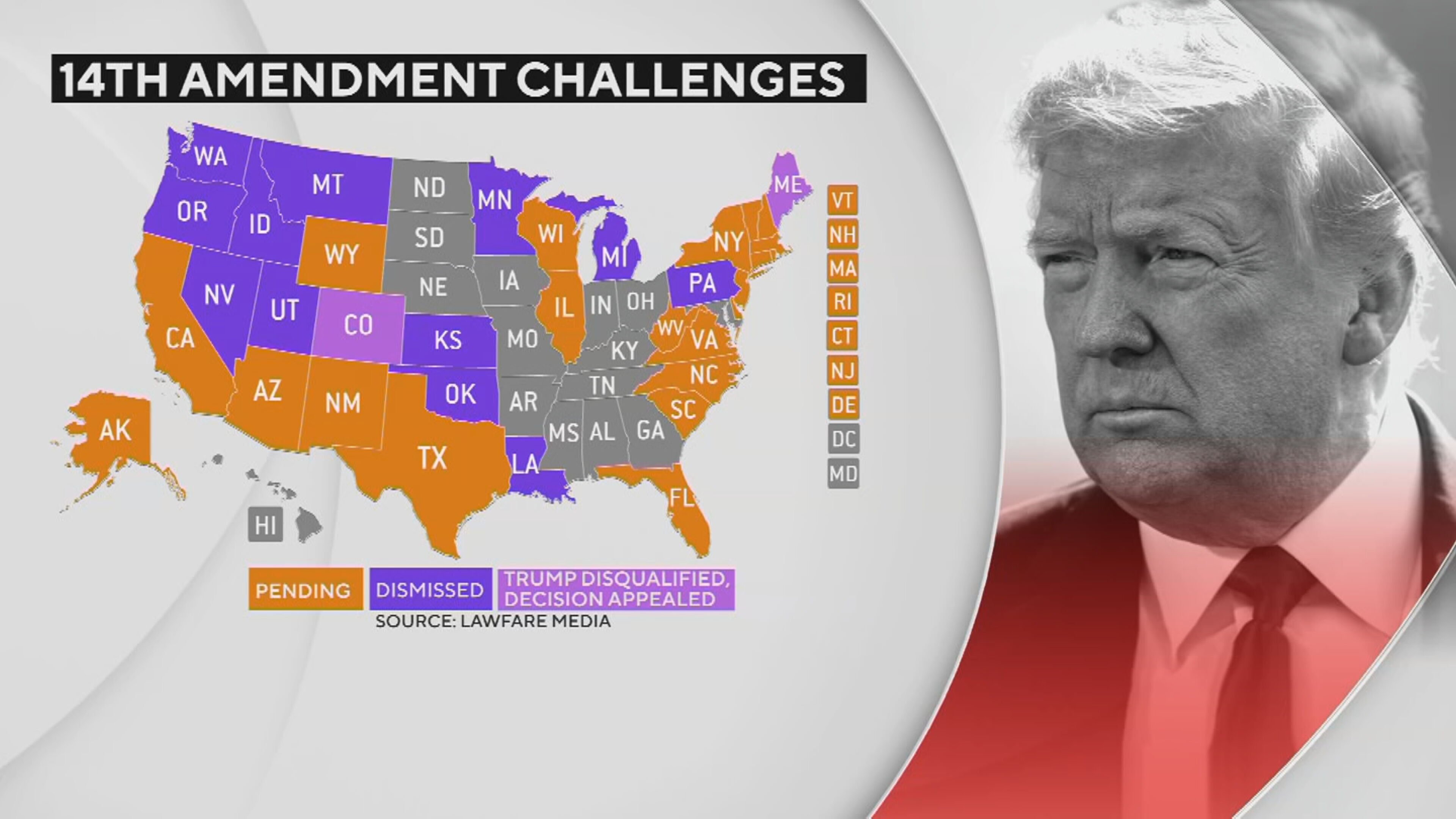

Supreme Court Seems Skeptical Of Colorado Decision Ruling Trump Ineligible For 2024 Ballot

The Supreme Court seemed skeptical of the idea that Colorado can exclude former President Donald Trump from the state's primary ballot, with justices on both sides of the ideological spectrum warning of the consequences of ruling him ineligible for the White House.

The case before the high court, known as Trump v. Anderson, involves whether Trump is disqualified from holding the presidency again because of his conduct surrounding the Jan. 6, 2021, assault on the U.S. Capitol. The dispute that puts the nine justices into new legal territory, and their opinion could have sweeping implications for the 2024 presidential race.

The case hinges on Section 3 of the 14th Amendment, which bars officials who have sworn to support the Constitution from serving in government if they engage in insurrection. The provision was enacted in 1868 to prevent former Confederates from holding office and laid mostly dormant for more than 150 years.

Over two hours of oral arguments, the justices questioned the notion that states can determine whether a presidential candidate is disqualified from holding office under Section 3 and thus exclude them from the ballot. At one point, Chief Justice John Roberts said that argument was "at war with the whole thrust of the 14th Amendment and very ahistorical."

"I would expect that a goodly number of states will say, whoever the Democratic candidate is, you're off the ballot. And others, for the Republican candidate, you're off the ballot, and it'll come down to just a handful of states that are going to decide the presidential election," the chief justice said. "That's a pretty daunting consequence."

Oral Arguments in the Colorado Trump Case

The case arose out of the lawsuit the Colorado voters filed in the fall, which invoked a rarely used provision of a constitutional amendment passed in 1868 that was designed to keep former Confederates from holding public office.

Known as the insurrection clause, Section 3 of the 14th Amendment bars an individual who swore an oath to support the Constitution and then engaged in insurrection against it from holding federal or state office. The voters claimed that Trump instigated the Jan. 6 attack as part of his efforts to subvert the transfer of presidential power after the 2020 election, and therefore is disqualified from holding public office and appearing on the state's primary ballot.

The Colorado Supreme Court agreed, and issued a 4-3 decision in December concluding that Trump is ineligible for the White House and should be disqualified from the ballot.

The court placed its ruling on hold and Trump appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court. His attorneys have raised a number of issues for the justices to weigh: whether state and federal courts can even enforce the provision without legislation from Congress; whether Section 3 applies to Trump as a former president; and whether he engaged in insurrection.

Jonathan Mitchell, a Texas-based attorney, argued on behalf of Trump, and Jason Murray, who practices in Denver, appeared for the six Colorado voters who challenged Trump's eligibility. Colorado Solicitor General Shannon Stevenson also argued for Secretary of State Jena Griswold.

Mitchell laid out his case before the justices during oral arguments on Thursday. He repeatedly pointed to an 1869 case involving a criminal defendant named Caesar Griffin, believed to be the first major judicial opinion on Section 3. Chief Justice Salmon Chase, serving as the circuit judge who heard cases in Virginia, held that the text of Section 3 was not self-executing and therefore could only be enforced through an act of Congress. Mitchell said Congress relied on that decision when crafting a law in 1870 that instructed federal officials to enforce Section 3.

Mitchell argued that Griffin's case, and Congress' subsequent action, shows that states don't have the authority to enforce Section 3 — and decide that a candidate is disqualified from office — unless Congress grants them the power to do so.

Justice Sonia Sotomayor pointed out that Chase's ruling did not set a precedent for the Supreme Court, and noted that he contradicted his ruling in another case. Justice Elena Kagan asked what Mitchell's argument would be without Griffin: "Suppose that we took all of that away — suppose there was no Griffin case, and there was no subsequent congressional enactment — what do you then think the rule would be?"

Mitchell replied: "Just a matter of first principles, without Griffin's case, it's a much harder argument for us to make, because normally — I mean, every other provision of the 14th Amendment has been treated as self-executing."

Mitchell also argued that Section 3 cannot be used to deny Trump access to the ballot because it prohibits a person only from holding office, not running as a candidate, or winning an election. Section 3 allows Congress to lift the disqualification for insurrectionists, and Mitchell said states cannot declare a candidate ineligible for office when the possibility of receiving a congressional waiver still exists.

Later, under questioning from Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson, Mitchell said the events on Jan. 6 did not rise to the level of "insurrection."

"For an insurrection, there needs to be an organized, concerted effort to overthrow the government of the United States through violence," he said. "This was a riot. It was not an insurrection. The events were criminal, shameful, all those things, but they did not qualify as an insurrection as that term is used in Section 3."

Murray, appearing for the Colorado voters, urged the Supreme Court to uphold the Colorado ruling, arguing that Trump betrayed his oath to preserve, protect, and defend the Constitution by inciting a violent mob to attack the Capitol in an attempt to stop the counting of electoral votes cast against him.

Justice Clarence Thomas asked Murray for historical examples of states disqualifying national candidates from the ballot under Section 3. Murray could point to only one — from 1868 when the governor of Georgia refused to certify results of a congressional election — and Roberts indicated that Murray's reading of states' power to enforce Section 3 ran against the rest of the 14th Amendment.

"The whole point of the 14th Amendment was to restrict state power," he said, pointing to several other sections. "On the other hand, it augmented federal power under Section 5 — Congress has the power to enforce it. So wouldn't that be the last place that you'd look for authorization for the states, including Confederate states, to enforce, implicitly authorized to enforce the presidential election process?"

He continued: "The narrower power you're looking for is the power of disqualification, right? That is a very specific power in the 14th Amendment and you're saying that was implicitly extended to the states under a clause that doesn't address that at all."

Murray responded that Section 3 has not been used since the 1870s because "we haven't seen anything like Jan. 6 since Reconstruction," adding that "insurrection against the Constitution is something extraordinary."

Justice Brett Kavanaugh disagreed: "I think the reason it's been dormant is because it's been settled understanding that Chief Justice Chase, even if not right in every detail, was essentially right, and the branches of government have acted under that settled understanding for 155 years. And Congress can change that … but they have not in 155 years, in relevant respects."

The oral arguments lasted just over two hours. Both sides of the case have urged the justices to rule quickly.